1 Corinthians 13:1–13

We typically relegate 1 Corinthians 13 to the province of sentimentality, using it at weddings and even funerals to do the emotional heavy-lifting for us. While Paul’s exposition on the significance and nature of love is entirely appropriate for those occasions, limiting it to those type of events is not. The understanding of love in 1 Corinthians 13 is a radical ethic that we need to embrace in every part of our lives — it’s not just the proprietary of loved ones gained and lost.

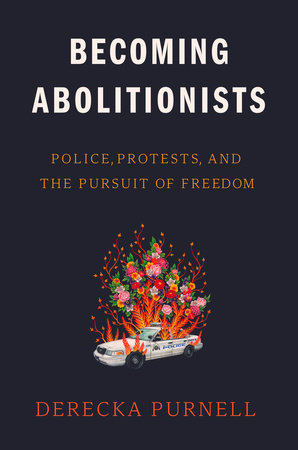

Abolition is an ethic of love, one that rejects patterns of retributive violence and vengeance that dominate much of the world. The entire police state and prison industrial complex is based on an ethic of punishment, fear, and profit. Punishment because the system believes (or teaches us to believe) that punishment will satisfy the demands of justice and somehow make up for whatever crime the system claims has been committed. Fear because the system believes (or teaches us to believe) that police and prisons deter criminality rather than create and expand it. Profit because the system knows (and wants us not to know) that there’s money to be made in prison beds, militarized police, and complex legal systems.

1 Corinthians 13 rejects all of those things: punishment, fear, and profit.

In particular, Paul rejects rejoicing in punishment, itself a “wrongdoing” (v. 6 NRSV) meant to correct another “wrongdoing.” Instead of an ethic of punishment, an ethic of love rejoices in telling the truth (again, v. 6), being patient and kind (v. 4), and not embracing resentment (v. 5). Systems and ethics of punishment obscure the truth of what people need to change and create a culture of resentment toward those who have experienced the systems of police and prisons.

Elsewhere, Scripture says that love is the rejection of fear, the currency of police and prisons. “There is no fear in love,” 1 John says, “but perfect love drives out fear, because fear expects punishment” (4:18, CEB). Fear reinforces the things that love is not. Fear is rarely patient (v. 4), it does not prioritize kindness (v. 4), and it certainly does not hope (v. 7).

Paul’s ethic of love here, too, presumes that profit is not the point. Before you can even entertain the idea of love, Paul presumes that acts of charity are second nature (v. 3). Systems of fear and punishment do not presume the sharing of resources, mutual aid, or any sort of generosity. Yet these things seem to be part and parcel of the culture of love Paul describes in 1 Corinthians 13.

Love is eternal, according to Paul. It never ends. If that’s true, we can have hope that love will outlast systems of punishment, fear, and profit. We exist in an imperfect world dominated by these ethics, but Paul promises that we will fully see love in time (v. 12). In the meantime, with that hope we need to act with love and that means letting every aspect of our lives (both individually and collectively) be governed by love. That means police and prisons have to end.

Wesley Spears-Newsome (he/him/his) is a Baptist pastor and writer in North Carolina.